Run BMC - Business models, it’s tricky

How to create them, and why they're ready for remixing

If you’re interested in innovation and strategy then ‘business model’ probably lands near the top of your toolset in understanding businesses and their ecosystems. But the idea of a business model is pretty new - and the now-ubiquitous business model canvas even more so. In fact the google ngram record for ‘business model’ looks a lot like a hockey stick that only started at the turn of this century. But that hockey stick is so steep that today, people can forget that a model isn’t reality, it’s simply a way of understanding what’s going on in the messy world of the everyday for businesses big and small.

This piece from Toby, the first of several, is super useful in explaining the power of a model - how it can enable us to codify, analyse and reflect on something that previously simply existed in the intuition and imagination of the founder. And then to take the next step - to use it as a diagnostic and strategic tool, both in understanding the journey from start-up to successful business, and beyond that, to business model innovation in the face of competitors who will likely come at you with a completely different configuration of business model to your own - Tom

Business models are real and how well or poorly they are designed is an absolute guarantee of a success or a failure, yet the concept has a Cosi Fan Tutte quality, “like the Arabian Phoenix, everyone says it exists but no one knows where it is”. Maybe when you stick the word “model” on anything it sounds like some bullshit simplification of real life. Yet they have a supremely consequential impact on a business. Businesses literally don’t exist unless they have one, getting it right and keeping getting it right is the only way to profitability (barring some Gangster Capitalism),

At least partly due to this conceptualisation and related ambiguity it feels like business model innovation is a poorly explained and poorly applied lens to what is a very real challenge. And this despite the trotted out bugbears of Kodak, Blockbusters et al as the prime suspects in a round up of business tropes for their inability to actually see a new business model. . Somehow businesses on the one hand get it, and on the other don’t really do enough about it.

What I want to do is bring a bit of clarity on what I believe a business model is and, in doing so, hopefully make it a clearer and more useable term. Every business has one, every business needs to think in parallel about tightening and shifting it, and it should be something that everyone in the business is able to get, make better and comment thoughtfully on.

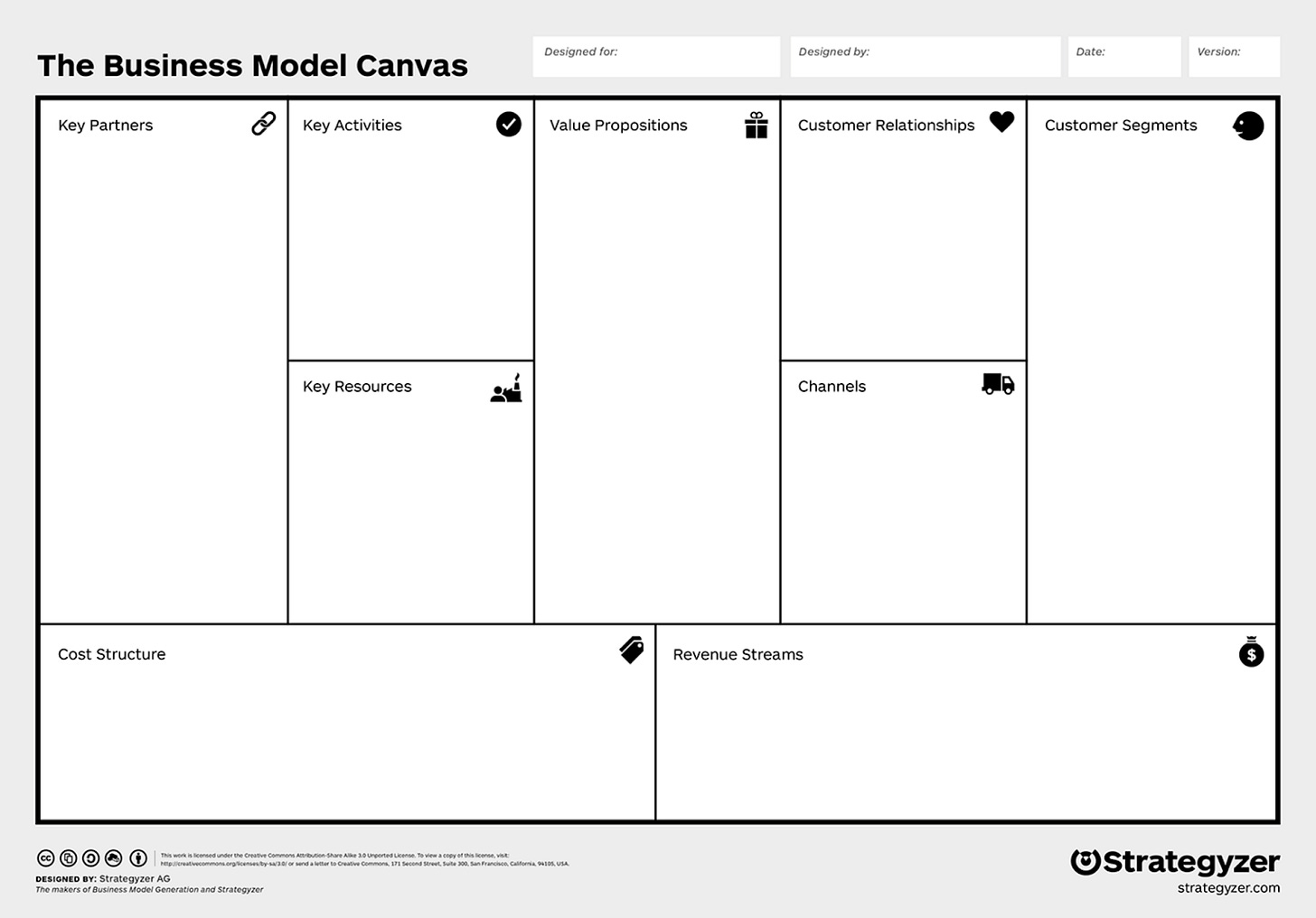

For clarity we use the Business Model Canvas, the tool designed by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur in their book “Business Model Generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers and challengers”. It is the ubiquitous tool to characterise what a business model looks like. It helpfully shows the building blocks of a business.

I think at least part of its effectiveness is that it doesn’t characterise typical functions, but rather ways of framing. You can see where the functions sit, but by not going down a functional route it stops everyone just finding their box.Whether the thinking was explicitly with this in mind or not, it at least acts as friction to mindlessly going down the functional route. If I am in marketing, sure I get to look at customer relationships and channels, indeed the whole right side is front office. But it does encourage me to look at what activities I need within the organisation ( e.g data flows) and resources ( what sales force skills do I need to interact with who and why) etc. A functionally dominant route leads to the self justification of existing functions and ways of working, which means your business model will just be a version of today, you aren’t, for example, going to decide you don’t need HR (Octopus Energy) if they are one of the designers.

Business models, in this format, are a bunch of component parts that you need to bring together to make a business work. Like a sports team, for it to function effectively you need to have all the parts.Knowing what the parts are is a necessary, if insufficient element of building. Knowing a football team has a goalie, two backs, etc isn’t enough to design and execute a great team strategy and way of playing.

Demystifying the elusive phoenix - what is a business model?

Since businesses have been around since forever, it is obvious that so have business models. If you want to sell something you need a business model. It’s not really a model, it's just the way the business is set up in the real world. Reframing it as a model helps to extrapolate to a working and manageable way of understanding how the whole thing functions so you can hold it and turn it around. In the real world it is glimpsed through the thousands of everyday activities and decisions, agreements, contracts and learnings but that is way too rich and dense to figure out, so you need an abstraction.

It is the structure that allows the thing you are selling to come into existence and then be delivered to your customer. A thousand years ago it wasn’t a source of reflection or evolution:, build it, make it work and keep it working. Merchants didn’t spend their time reflecting on business models, they set up supply chains, customers, pricing and so on. The “model” part is just an abstraction for ease of understanding, and by making us consciously aware of it we can actually reflect on it.

The mundanity of this fact hides an interesting reality, every business came up with a business model to get going. Every large business today at some point in its history conceived of a high performing business model that allowed it to exist and then buffed and polished it effectively to drive the profitable growth that got it to today. Business models are literally everywhere, good ones, bad ones, new ones, old ones.

The emergence of the conscious reflection of business models has been driven by the significant growth of startups and the challenge they represented and still represent to the established businesses. These new businesses challenging just didn’t look like the old ones, and people immediately recognised it wasn’t just the products they were selling, but how they were set up. Start ups were searching for new business models as a way of delivering their new offers, Steve Blank’s definition is “ a startup is an organisation formed to search for a repeatable and scalable business model”.

There’s only one first time - creating a business (startupland) and iterating a business (everyone else)

Business model innovation comes in two forms, creation and iteration. We will look at business model creation (what startups do, what Steve Blank refers to) as I think it brings to life intuitively what a business model is.

At this point I want to distinguish business model creation ( being a start up), from business model iteration (you figuring out how to change your business because the world is changing) , for two reasons. The first reason is creation is linear, whereas iteration is iterative. This means you create only once, right early on when you go from a maybe company to a real thing. Iteration is when you are in the realities of “ adapt or die”.

The second is because creation is way easier than iteration since you have a blank sheet of paper, not an existing business model you are trying to challenge. When you have nothing, everything is possible, you can just imagine what would be a great answer. When you already have something you have a set of mental constraints (the way we do things here), political (back to the functional point earlier, functions are unlikely to define themselves out of existence), and rational ones (the existing channels, the stock price, the technical debt, etc.). But let’s start at the beginning, a very good place to start. The startup “caterpillar to butterfly” journey brings clarity to what the role of the business model is.

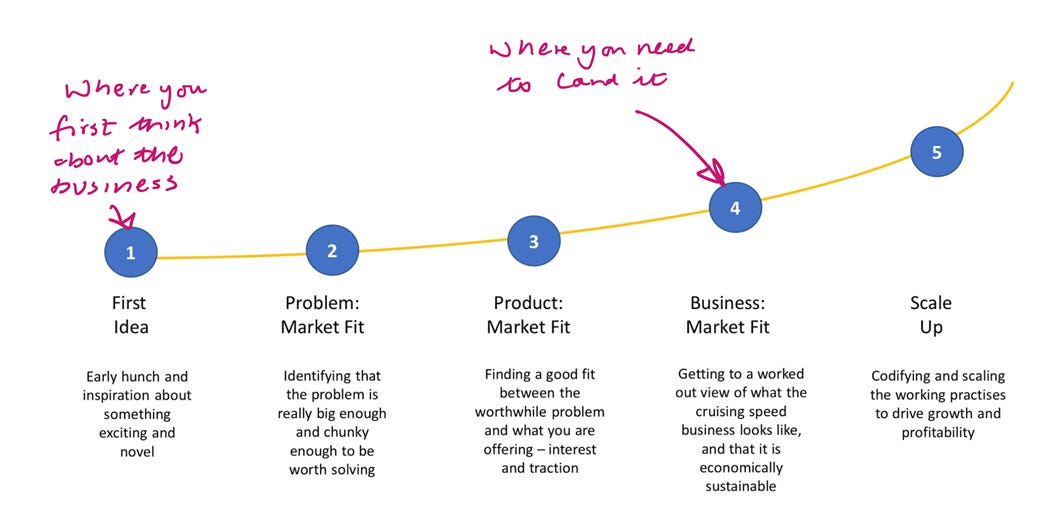

Finding the right product

Startups have to come up with a great product, this is the product:market fit stage. A great product:market fit clarifies and shows an unmet or poorly met need for customers,, a strong desire to solve the need and significant upside potential. During this cycle the startup is looking to adapt and evolve the offer to meet a (changing) target population so what you are pitching fits really really well with enough of the needs of the target population. You know when you have a good product: market fit turns up in purchase, repeat purchase and recommendation.

Finding the right business

With this solved the business has traction and revenues. It has a thing the market wants. The product needs to be made, shipped, sold, promoted, etc. this is what the business model is designed to do, to work out how all those things happen. But not just how they happen but happen effectively so there is a strong business model:market fit. This is way more complex and gritty than the product market fit because the number of moving parts has gone up considerably, creating more challenges of interdependencies.

A great business model: market fit means not just maintaining the great product:market fit but also delivering the product at super hi fidelity against the promise of the value proposition at a price, place and experience the customer expects AND ensuring enough value is captured for the business itself that drives sustainable (profitable) longer term growth. Getting something built that customers love is one thing, getting them something they love that has a whole way of making, shipping and promoting it while having enough money yourself to grow this business is a qualitatively different sort of challenge.

This also brings to life the challenge. Whereas there is a relatively singular need: product type fit, for the wraparound business model the complexity is several orders of magnitude larger. This is because there are many more elements. It involves, sourcing, assembling, making, maintaining, controlling, shipping, pricing, positioning, delivering, supporting, financing, and more. Each of these activities is an expertise in itself and each needs to coordinate with the other so they all fit together. Choices in one area impact outcomes elsewhere. It is a search for the best combined fit across multiple dimensions, not the best part for each added up. What sales approach suits the product, what speed of fulfilment requires what production, what end user expectation requires what sourcing, and so on. This is a hard two inches question that is easy to get out of whack, just look at the Oatly story we commented on in the previous Looking Up Looking Down.

At its simplest then, the business model is the product wraparound. It is what makes the product exist in the hi fidelity way that it delivers the promise and in the high value it offers the customer. It also ensures the business sustainability and so product longevity. The product drives revenues (no sales without a product), the business model drives profitability (no margins if you can’t design the business right).

The methodology is similar to finding the right product, just on a bigger and way more complex scale. The company is testing and trialling out different approaches to create a profitable business, the right go to market strategy, the right supply chain mix and manufacturing process and technology, the necessary cost base, etc. Once it has figured this out (that’ “once” is doing a lot of heavy lifting) and can see its route to cruising speed profitability it then needs to stop exploring and start codifying.

Locking down the right business

Codifying is taking the practices used in a temporary capacity and locking them down to have a repeatable and scalable process. This is where a startup stops being a startup and becomes the business it seeks to be. Every startup wants to become an established business, that’s where glory, money and kudos sit. Locking down means this codification of key practices and the translation of this coding into ways of working through formalised processes, contracts and structures. This is the hard graft of becoming a business, not quite so sexy as the freewheeling days of constant exploration and creation. But the money starts here.

This is now a stable thing. We know what the business is, we can see sustainable profitability. The business will continue to drive its growth and success by improving the moving parts, and creating areas of expertise that can make the business parts even better, e.g. deeply informed manufacturing improvements, adopt new marketing skills, refine the channel approach. This is the time when functional expertise comes to the fore and is critical to allowing the business to grow profitably. You want the strong marketers, the production experience, the finance etc to bring their knowledge and knowhow to making the thing better.

As an aside, the fundamental importance of having a joined up business model is put in stark relief in the current market conditions, post free money. A lot of seemingly great products such as Getir, Peloton, Carvana (OK, TBH, I don’t think Getir is a great product) have become seriously unstuck because they don’t have a functioning business model. When the only answer to growth is an endless supply of someone else’s money you haven’t got a business model.

Not having a business model isn’t a crime, lots of businesses can get investment whilst they figure it out and have a directional sense of where it is. However not thinking about your business model or declaring victory on the aircraft carrier too soon does strike me as criminal negligence. You have to have a view of where profitability actually sits and how the business assumptions and joined up thinking that show why that is a plausible thing, not a fancy formulation of fake routes to profitability with creative ways of describing “Adjusted EBITDA” (described archly by an anonymous Moody's Analyst as "Eventually Busted, Interesting Theory, Deeply Aspirational.") which have been so common.

Personally I don’t think Getir has one at all on any operational level, I think Peloton designed itself around some heroic future assumptions but there is a business in there which is much more prosaic than it wants to be, and Carvana is probably suffering from a particular set of market conditions that make it interested but stretched.

Good to Great (business models)

That then is an effective business model, where it is an enabler. A wraparound structure to create sustainable growth. You are up and running.

However I think some really smart business model thinking does three more things. Firstly it doesn’t just ensure the faithful and hi fidelity replication of the offer, it actually amplifies this. Secondly the reflections on the business model elements can actually change the nature of the offer, shifting elements of the business model into the customer value proposition so they become value creators. And thirdly, they contain within themselves the ability to evolve. I’ll save some deeper reflection on this last one for a future date as it's a big topic, but to quickly give some examples of what I mean

Amplifying the offer - Zara (or Shein now) has an offer built on frequency of season, the classic fashion industry operating on 4 seasons a year, Zara somewhere between 3-5 times that. The value proposition for Zara is something like accessible fashion, fast (it goes from being seen a fashion show to something replicated in the store very quickly), variety (more likely to find something new in the store when I go in ) and personal (less likely for someone else to have it).

Zara are able to achieve this through the design of their supply chain (manufacturing, forecasting, stock management, feedback loops, etc.) , that other fashion businesses hadn’t implemented, allowing stock turns of 12x a year vs 3-4, and SKUs of 11,000 vs typically 2,000 - 3,000 (for a detailed description go here). This supply chain approach (then copied and technology amped by Shein + a bunch of other stuff - see this article), accentuates the offer itself and improvements in the underlying business model continue to enhance the offer, the promise to end consumers.Bring the business model into the value proposition - this is more conjecture, but when I look at Dollar Shave Club, it seems to me the offer wasn’t just razors. It is offering razors + convenience (home delivery, no more adding it in/ not adding it in to your weekly shop intermittently) and knowledge (you need to change your blades every 6 weeks). It solves for a broader and deeper set of customer needs, and in doing so it allows the business to monetise more of its business model.

This meant the subscription (revenues model in the BMC) and channel (DTC, delivery) all became part of the actual proposition. The other razor companies saw razors, but consumers saw so much more. The competition saw the market as razors and struggled to understand and replicate, as well as being locked in an existing business model where the channel strategy was an external retailer, so difficult to cut them out without consequences.

Design for significant change - this is the explicit recognition that you know your business model isn’t going to last forever. In my head this is the moment where Batman gets the crap beaten out of him by Bain, Bain tells him “Ah you think darkness is your ally? You merely adopted the dark, I was born in it, moulded by it” . This is Amazon vs Barnes and Noble, Airbnb vs IHG etc - businesses that understand that constant adaptation is the necessary build requirement, not just getting it right once.

Understanding the possibilities of today’s technologies and how they disrupt what exists, is also to understand how technologies will continue to do so. My hunch of companies like Amazon, is that they have designed a business that is modular, so they can adapt parts but not worry about others, the whole business in evolution, but specific areas acting as points of stability.

This allows a culture of constant challenge and new business generation, leveraging parts of the business to make a new offer, the best examples being AWS, and the marketplace for 3rd parties.

I worked on an SAP project, building the enterprise architecture and it was designed like old school businesses think, minimal slack, everything super efficient and all locked down to ensure stability. It was one massively joined up thing a crazily tightly coupled system, where every piece of data needed to be entered to make the system work, changes to parts required changes to the whole. It guaranteed optimal performance against all the conditions in which it was designed.

Its only problem was when those conditions changed. At the time web based solutions were emerging and you could see immediately they were loosely coupled, allowing flexibility, interoperability and ease of use. This has to be the way businesses need to think about how they design for the future. It exists in software architecture, it should exist in organisational architecture.

This is a starter for ten, a monkey’s paw of an article that anticipates a lot more reflectiveness on business models, why they are hard, why now, how to build and so on, so expect them. What I wanted to do here was to give some grounding on how we see business models and their purpose, hopefully it gives enough clarity to realise they aren’t some obscure theoretical construct but rather something real, practical and critical.

This triggers some broader reflections on what to think about, what to reflect on and what to watch out for:

The business model space gets a lot of big theory that makes it far too overblown and prone to “in theory, practise and theory are the same thing, in practise they are different” type problems. Business models are just how businesses are run, from the newsagent down the road to Tesla and many survive without grand theories. Don’t get me wrong, theories are how we abstract from a challenge to understand patterns so we can intervene, they are absolutely critical to businesses evolving, even if they are back of the cigarette packet theorising. But they can be used to hide a lot of guff behind big theory (to my mind Klarna, Getir, etc. As Nietzsche once said “they muddy the water to make it seem deep”. The complexity shouldn’t be in the theory (which should provide helpful frameworks to intervene), it should be in the build and effective execution.

It lives solidly in the ten thousand feet and two inches. It needs a bit of a step back so you can work out what are the (currently) critical moving parts and where to intervene rather than being lost in the weeds. But it is always in the detail of the business model that you can find if it is “nonsense on stilts”. If you can’t explain in detail a single customer case from awareness to repeat and a single product journey from conception to being used, then you don’t have a business model.

Figuring out a business model needs a lot of rigour and numbers so you can work out whether it is internally coherent against the promise. Data gives you good reasons to believe in certain outcomes. But it is not conceived through analysis, it is built on a tightly joined up story of solving for a problem in the world and wrapping a way of delivering that around it. The strength of the story is the same as that of a movie: do all the characters have plausible motives and do they act in line with their motives, or are there bits where the suspension of disbelief is too big? That’s your bullshit indicator going off telling you there is something flawed and incoherent about the business model.

It is a definitive “strong opinions lightly held” approach. You need a tight and confident answer, but it is likely to be wrong, given the multitude of moving parts. Having an opinion asks of you a tight logic and coherence, so when stuff goes different to what you expect you can track back to the weakest assumption and recalibrate. If your thinking is flaky you won’t have a logic of change and data will be noise, not insight.

It isn’t a classic business optimisation project with a known timeframe, budget and outcome, much as consultants would like to tell you otherwise. Startups have burn rates and runways for reasons, they design for flexibility and adaptation, for pivots and tweaks. This is going back to the first experience of the business when it was created and the possibility of it not existing was real. When a few people came together to imagine something new. To point d) above, you are highly likely to be wrong. I remember meeting with a bunch of startup founders, and one of them talked viscerally about wanting to be punched in the stomach everyday on where he was wrong so he could figure out where to change.

There isn’t a business innovation question that doesn’t benefit from at least a cursory glance at the business model, what if we loosened a few of our criteria, how different an answer could we create? How much of this is actually accessible through what we have with some tweaks? At worst it is a little more time (but with a little more wisdom) at best it creates a new path. So even for the smallest product change, it is worth at least entertaining what the business wrap around could look like.

Rich, insightful stuff! Two things lurk just below the surface of this piece that I really like…

Firstly, the shift from product invention to business model innovation - one might argue that the 20th century was the century of product invention, where the heroes were the inventors of new technologies inside the products that shaped our world - the internal combustion engine, the aeroplane, the transistor, the radio receiver. In this product-centric world, business models evolved relatively slowly. The 21st century has become the century of business model innovation - where the invention comes not so much in the product or value proposition, as much as it does in the whole business model: the delivery channel, the customer relationship, the revenue model or the supplier and partner ecosystem, the whole thing together. The business behemoths of this age are business model innovators more than they are product inventors - Jobs, Bezos, Musk, Zuckerberg. Surface-level analysis of ‘famous’ business successes get stuck on the product invention, nuanced views will see the interconnectedness of the business model innovation beneath.

Secondly, the idea of Business/Market fit - this is profound. Most innovation thinking will major only on problem/market and product/market fit but (see above) it’s the whole, messy, fallible, human-reliant business that will actually succeed in delivering that product, at a sufficient margin to enable survival and perhaps long term growth. - Tom