Run BMC - Ooh whatcha gonna do

Do it like a VC. Not.

Speed of change, disruption, creative destruction. The language of business in the past decade has increasingly become the language of transience. No sooner are you at the top of the pile, than you should worry about the rapid descent awaiting on the other side. So what will it be, stick or twist? The answer for our times seems to be a perennial ‘twist’: roll the dice, lean into the change. But how to do it well? NOT by innovation-washing the problem away, as Toby shows here - but rather by thinking about the relatedness of your innovation efforts to your core business, Packed with good examples and tips for how to make real change, this is 10,002 in a nutshell - enjoy! - Tom

We have talked about business models, what they are and how the need for business model innovation arose from a confluence of events and trends, in particular the impact of technology in accelerating business building. This creates lower predictability in the business world, what Mervyn King and John Kay refer to as “radical uncertainty”. The scope to address these changes shifts from internal improvement to an evolved understanding of where the business fits in the world, and this drove awareness of the need to look at business model innovation.

The risky flipside of all this business model thinking is that it becomes the next thing with companies jump from one “plug and play” approach to another. When the current business fixing approach (reengineering meets digital meets product and service innovation) shows reduced impact the businesses look for the next silver bullet. The answer, as we have talked about previously, was to look at the world of business building evidenced in the VC/ startup space.and just cut and paste this’

And this is where we are now, too many large businesses have gone off and built their own version of corporate venturing. I have had countless conversations with companies where they come with an ask on how to build a venturing unit. When you ask why, what are they solving for, the answer is just they want one. Venturing in whatever form is a tool not an outcome, it needs something to solve, yet somehow it has become default “disruptive innovation”, some version of innovation washing that is meant to project a dynamic business grappling strategically with the future.

Unfortunately this is a real elephant's graveyard, and after the fireworks and marching bands of setting this up and after the excitement dies down, these incubator/ accelerator/ venture units are quietly taken behind the woodsheds about 2 years later and killed off when costs are rising and sales not materialising. This mercy killing is a mix of misalignment of intent and a lack of due diligence.

Preparing the ground

The misalignment happens when the corporate talk of the need for disruptive innovation is either poor soil or poor groundwork.

Poor soil is when the talk of disruption is favoured by a few but lacks broader consensus and commitment across the business. This means it risks being flavour of the month, but after the shine has gone and the innovation is in the slog of the day to day, a change in leadership, a change in business performance and /or the inevitable need for more investment appears, the lack of strong roots leads to the inevitable march behind the woodshed.

Poor groundwork is where a business leaps to some venturing model because it is easy to pitch and comes with a nice shiny cover that is potentially eye catching to employees and the market. But the thinking lacks any strong consideration of the context. Venture models are particularly popular with consultancy companies because they have defined outcomes, can be pretty plug and play, and come with the mix of sex appeal associated with startupland/VC world, where managers see high value and rock star appeal, and the learned lessons can be well packaged. It is any port in a storm.

What this approach lacks, not least because companies can be both impatient to get to answers and also can believe their own diagnosis, is a reflective period to explore the nature of the ambition, the nature of the context and the possibilities inherent in the existing business. Too many innovation projects generally, never mind disruptive questions, seek to significantly compress the grounding and discovery work at the start and rush into the ideas phase. Discovery is too often seen as stuff already known, and after all shiny exciting ideas is where the fun is. It’s also that annoying “just do it” meets “move fast and break things” trope that gets rolled out about being innovative.

The consequence of either poor soil or poor groundwork is little work is done on understanding the existing business model, how it fits into the broader market and what its possibilities are, so ideas for new possibilities spring from nothing, no understanding of why us, what we are leveraging, or what we are constrained by. Which means you risk ending up with generic floating ideas that could be owned by anyone. This is exactly where an existing business doesn’t want to be, since it will always lose out on pace and flexibility while having no way of playing to a strength. .

Getting behind the extremes

What we want to explore here is a more shades of colour view of this than its either “business as usual or some funky fussball incubator set up. To be clear incubators can be the answer, its just unlikely as there are so many alternatives before leaving the rest of the business behind. When the answer is to set up a completely new business this comes with the greatest disruption and the least exploitation of the existing.

The r incubator route is basically to assume the existing business has no value and the only answer is just zero base the entire new business. If you are a startup this is obvious. You have nothing and need to get to building something so there are no alternatives, but if you have an existing business is this really the only answer to build a completely new business?

What an existing business has is what a startup wants, a stable revenue and profit generating structure that was optimised to deliver consistent value. Sure, businesses are seeking innovation pathways because the answer they have no longer delivers the value they seek or need. But there are two important things to bear in mind. Firstly this existing business has successfully solved for a problem already at least once in its past, it has grown up from an idea into a multi million dollar/ euro business AND it has worked out how to make that sustainable. There is muscle memory in that. Secondly it has expertise, assets, people, ways of working, technology, deep understanding of customers, loyal customers etc that function together and contain significant value both separately and how they work together. This heritage of transition and this existing set of assets are all worth exploring and exploiting surely, before discarding the whole shebang and just heading off to startupland.

It is this legacy and mix of assets that a business should turn to when confronted with a performance challenge, and it is from this it should at least start to search for a path forward.

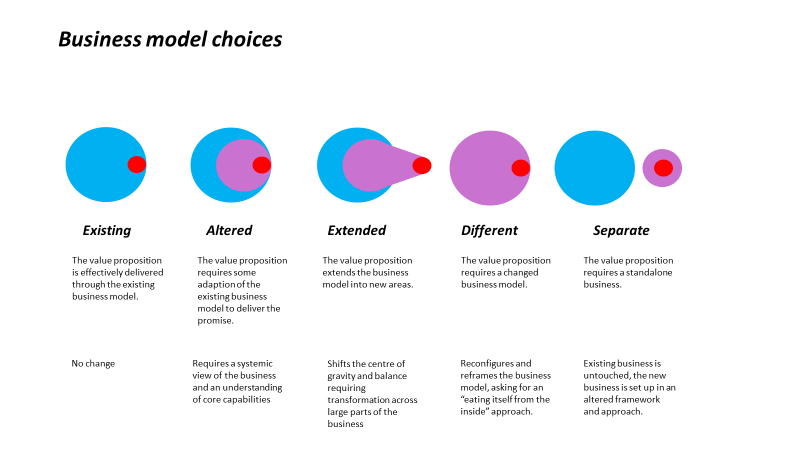

When we look at business model change we look at it across a spectrum of possible outcomes. This ranges from the improved exploitation of the existing business model all the way through to a venturing unit. The likelihood is 95% of answers sit somewhere short of a full separation and new business.

Lowest risk/ highest return

Considering the business model is pretty much always a worthwhile reflection since it opens up options, and often leads to just better innovation since it asks questions of innovation that aren’t just new product or service. But the answer is rarely to jump from running the day to day business to leaping into building your own start up version. This is the most disruptive to the existing business and has the highest risk. There are so many versions of business model change that go from the slightest tweak to the start up, that all should be considered before leaping to the most radical.

As this newsletter has hammered on about, existing businesses are not startups and therefore need to be smarter about what they take from the explosion of venture capital backed innovation. Instead businesses need to spend sufficient time understanding the nature of the challenge they have and their ambitions, to work out a lowest risk/ highest return type solution.

Lowest risk pulls the answers more closely to the existing business. This allows the business to leverage what it has. Any functioning business has

An existing set of assets, processes, technology and skills

A interaction with the market that has driven a loyal customer base and an awareness of customer needs

A (perhaps implicit) understanding of how the business fits together and how to effectively pilot this business through its complex ecosystem

A collective culture and set of behaviours that have synched together and know how to align

Etc

It is a complex, functioning organic whole and a repository of a lot of (perhaps under exploited) value. If a business can use as much of this as possible it has lower delivery risk (knows how to do a bunch of stuff) lower disruption risk (much stays the same), and lower market risk (investors understand what it does).

Highest return pulls the business to the other end of the spectrum. Something new and different to what is on offer today is more likely to fit an unmet need, drive longer term growth and create a competitive moat through a new configuration of business, technology and markets. This is literally the story of the successful startups to businesses we have seen over the last few decades such as Salesforce.com.

A spectrum of business model change

This resolution of risk and return will put a business somewhere along a spectrum, from finding a solution that actually exploits and favours the existing business model, to one where a business needs to create a new version of itself outside and away from the existing.

This is to nuance the choice between digital reengineering (make better not different) and incubator (change everything), both plausible and seductive because they are “this or that” type choices, but both unlikely as the best solution. Unlikely just because there is a whole spectrum of solutions that sit in between. It just an easier choice to make a definitive play for either end, and tends to be an easier buy because of the lack of nuance. Yet finding the right business model answer to the challenge is definitively nuanced and is worth spending enough time and effort in diagnosing and enacting.

Despite the seeming attraction to either end businesses have been extremely successful in finding their home along the spectrum, leveraging capabilities and assets, while imagining new offers and evolved combinations to change the underlying business in subtle and thoughtful ways.

Existing It turns out the new offer sits within the reach of the existing business. This is perfect, the business spots a new need and can design, develop and launch an answer that fits perfectly. There may be a shift in marketing, perhaps a change in the supply chain set up, but broadly the model can flex to the new offer without radical change and still provide the hi fidelity of support. This is smart use and understanding of an existing business model.

Hershey has seen a significant stock improvement, doubling in the last five years off the back of shift in their business. It shifted from chocolate to investing billions in building a salty snack portfolio including popcorn, cheese puffs and pretzels. “SkinnyPop was a seminal moment for us as a company” commented Ms Riggs, Chief Growth Officer. The business remains a snack company, and what Hersheys realised was that they weren’t selling chocolate they were selling Hershey’s chocolate and reapplied this functioning model to a new set of snacks. From a business perspective this meant leveraging existing retail relationships, exploiting a deep understanding of the value of the Hershey’s brand and how to manage a snacks supply chain. The change brought about a new suite of products, a different production process and recipe design, but the business looks, feels and operates to similar rhythms and similar core skills. This is a great reuse of an existing business model to continue to drive growth without busting out the business model.

Altered. The offer requires modification to parts of the business expressly, to be able to meet the new offer and the value it represents. This means changing some elements of the business, typically in the front end engagement, but continuing to exploit the broader capabilities and assets the business has. This allows the business a high confidence in the ability to deliver, and a shift into an evolved area of operation.

The Airbnb Experiences might be a good example of this. A new offer that requires different capabilities and a different market, but fits perfectly with the brand promise and reinforces the unique city stay experience. Experiences required a different marketplace set up, has a different sort of dynamic (management of class sizes, broader market, shorter cycles of use, etc). But it still drew on the same customers, operated with the same platform approach and engagement. It is not clear the extent to which Experiences has been a profit engine on its own or whether it’s key role is reinforcing the existing proposition by dialing up its uniqueness. What is clear is that the overall business has continued to grow strong. Q2 announcements show their most profitable quarter ever (net income of $379 million) and significant improvements in free cash flow ( last 12m the business has generated $2.9 billion in FCF, bringing total cash balance to nearly $10 billion).

Extended. The offer shifts the business centre of gravity in some way requiring a strong transformation across large parts of the business model. This will mean changing existing capabilities and adding new ones. Equally critically is will involve the altered relationship between parts, the challenge will be to ensure the total system of the business moves in synch in its future state, that you don’t have elements of it caught in a previous way of working that clogs up the works.

A good example would be the introduction of Electric Vehicles into the car industry. For a Ford this requires a different drive train, different marketing and customers, alignment with a very different ecosystem, a change in margins and in the underlying margins of spare parts. At the same time large parts of the assembly remain unchanged, the underlying model of tiered suppliers and outsourced expertise stayed, and the customer marketing and engagement was broadly consistent. If/when Autonomous vehicles turn up it will be a very different story.

Different. The changes actually require a complete change in the existing business model but allowing you to serve your existing market in a different and better way.

Rolls Royce to switch to hours of thrust is a great example. Driven by a changed need for how customers wanted to buy (not in clunky large capex investments irregularly) Rolls Royce hit upon an early as-a-Service model. It meant significantly changing their supply chain, taking on the responsibility for the maintenance of the engines themselves, service level guarantees around outcomes and the building of a real time data centre tracking all the engines in the world to monitor performance and need. Even engine design changed firstly to accommodate real time monitoring, secondly as a consequence of this they understand how pilots were actually using engines, and so could use this to redesign the engine. In this case Rolls Royce continued to invest and build its core capabilities in the underlying technology, and the evolved business model infact gave them improved insight into the real time use and performance, augmenting the overall quality and honing the understanding of the technology.

Separate. This is where the new business is not in the same industry, and doesn’t draw on the same market, but is the stand alone new offer and accompanying necessary business model. The mother company essentially has to build a lot from scratch, but even here it is leveraging some core awareness and understanding, a transferable set of skills.

The most interesting example here is probably Ping An, the Chinese Insurance company with a market cap of $220bn. It has launched a lot of successful businesses (over $10bn Market Cap ), but one really strong example is Good Doctor, the world’s largest tele-medicine business. It has 300m registered users and deals with 1m consultations a day, the model working through a digital triage platform that progressively moves from chatbot to text with physician to video to specialist.

The way Ping An works is to set up businesses in an entrepreneurial framework (external investors, management both externally and internally sourced, stock compensation models, etc.) and works with a strong bottom up ownership and drive model. Yet even here they clarify that these are not absentee landlord models with 3 or 6 monthly updates. Ping An is intimately involved in the day to day check in and performance, and acts with a lot of course correction.

Secondly these startup businesses need to be intimately aligned with the core strategic direction, and the company explicitly plans for technology investment and exploitation across the portfolio, as well as using the assets of Ping An to drive success. In the example of Good Doctor a critical element was using the 1.2m agents the business had for life insurance. These agents drove uptake and recommendation which ensured the rapid diffusion of awareness and use of Good Doctor.

Even here, at a separate business level, the model Ping An have so successfully used is the exploitation of the existing business to drive success of a separated business.

“It ain’t what you do its the way that you do it and that’s what gets results

As sung by the unsurpassable Ella Fitzgerald (and strangely later by the Fun Boy Three and Bananarama)

The need for considering business model change is a necessary part of reflecting on growth for any business today. However the risk is the only oven ready solutions are the ones coming from startup land. Impatience, pressure, politics and low awareness lead to businesses jumping on this solution. The real value, like in most things innovative, comes not from the sparkles of creative moments, but the sweat and slog of really getting to grips with what is going on.

What I love about the examples above is the extent that they demonstrate a mix of patience (Rolls Royce took 4 years to get their supply chain up and running), an active resistance to easy answers, a synthesis of existing and new that is unique to them that demonstrates strong investment nous, and what this typically means for the employees, where rather than the answer being something they are not, the answer is much more likely to come from what they do so well.